With the rapid expansion of new energy, mining, metallurgy, and electroplating industries, nickel pollution in water bodies has become a growing threat to environmental quality and human health. During industrial processes, nickel ions often interact with various chemical additives to form highly stable heavy-metal organic complexes (HMCs). In nickel electroplating, for example, citrate (Cit) is widely used to improve coating uniformity and brightness, but the two carboxyl groups in Cit readily coordinate with Ni²⁺ to form Ni–Citrate (Ni-Cit) complexes (logβ = 6.86). These complexes significantly alter nickel’s charge, steric configuration, mobility, and ecological risks, while their stability makes them challenging to remove with conventional precipitation or adsorption methods.

Currently, "complex dissociation" is regarded as the key step in removing HMCs. However, typical oxidation or chemical treatments suffer from high cost and complicated operation. Therefore, multifunctional materials with both oxidative and adsorptive capabilities offer a promising alternative.

Researchers from Beihang University, led by Prof. Xiaomin Li and Prof. Wenhong Fan, used the CIQTEK scanning electron microscope (SEM) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometer to conduct an in-depth investigation. They developed a new strategy using KOH-modified Arundo donax L. biochar to efficiently remove Ni-Cit from water. The modified biochar not only showed high removal efficiency but also enabled nickel recovery on the biochar surface. The study, titled “Removal of Nickel-Citrate by KOH-Modified Arundo donax L. Biochar: Critical Role of Persistent Free Radicals”, was recently published in Water Research.

Material Characterization

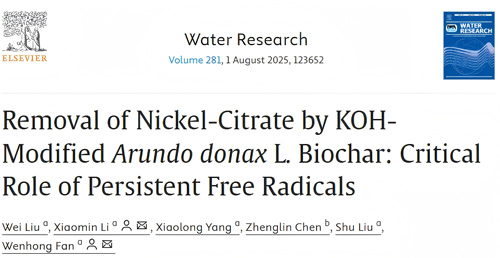

Biochar was produced from Arundo donax leaves and impregnated with KOH at different mass ratios. SEM imaging (Fig. 1) revealed:

-

The original biochar (BC) exhibited a disordered rod-like morphology.

-

At a 1:1 KOH-to-biomass ratio (1KBC), an ordered honeycomb-like porous structure was formed.

-

At ratios of 0.5:1 or 1.5:1, pores were underdeveloped or collapsed.

-

BET analysis confirmed the highest surface area for 1KBC (574.2 m²/g), far exceeding other samples.

SEM and BET characterization provided clear evidence that KOH modification dramatically enhances porosity and surface area—key factors for adsorption and redox reactivity.

Figure 1. Preparation and characterization of KOH-modified biochar.

Figure 1. Preparation and characterization of KOH-modified biochar.

Performance in Ni-Cit Removal

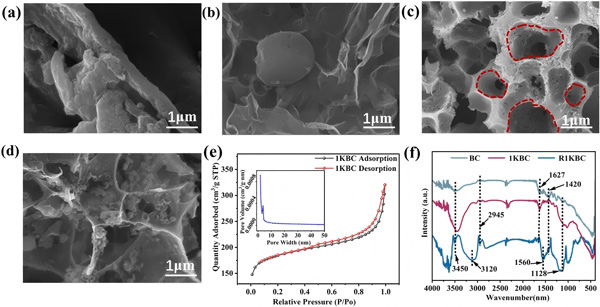

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Removal efficiency of total Ni by different biochars;

(b) TOC variation during Ni–Cit treatment;

(c) Effect of Ni–Cit concentration on the removal efficiency of 1KBC;

(d) Effect of pH on the removal performance of 1KBC;

(e) Influence of coexisting ions on Ni–Cit removal by 1KBC;

(f) Continuous-flow removal performance of Ni–Cit by 1KBC.

(Ni–Cit = 50 mg/L, biochar dosage = 1 g/L)

Batch experiments demonstrated strong removal performance:

-

At 50 mg/L Ni-Cit and 1 g/L material dosage, 1KBC removed 99.2% of total nickel within 4 hours, compared to 32.6% for BC.

-

TOC removal reached 31% for 1KBC, confirming that Ni-Cit undergoes complex dissociation followed by Ni²⁺ adsorption.

-

Even at 100 mg/L Ni-Cit, the removal efficiency remained above 93%.

-

1KBC maintained excellent performance across a wide pH range (pH > 5).

-

Phosphate significantly inhibited removal due to solution acidification and competitive complexation with Ni²⁺.

-

In continuous-flow tests, a 1KBC-packed fixed-bed reactor operated for 6900 minutes, treating 460 bed volumes, while maintaining effluent Ni < 0.5 mg/L.

Post-Treatment Material Characterization

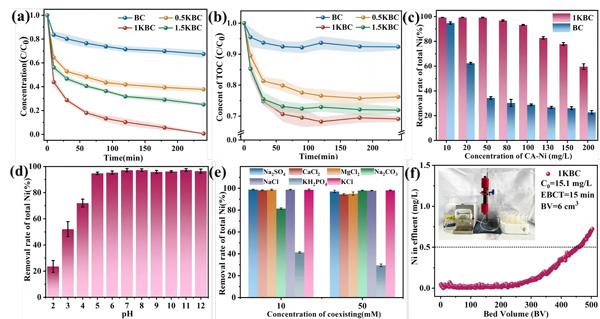

Figure 3. Morphology and EDS comparison of the material before (a) and after (b) Ni–Cit removal;

Figure 3. Morphology and EDS comparison of the material before (a) and after (b) Ni–Cit removal;

(c) XPS spectra of surface Ni 2p after the removal process.

Recovered biochar (R1KBC) showed:

-

No significant morphological changes.

-

Uniform Ni distribution confirmed by EDS mapping.

-

XPS spectra displayed both Ni²⁺ and Ni³⁺ peaks, direct evidence of oxidative complex dissociation.

EPR-Based Identification of ROS

Figure 4. EPR measurements:

Figure 4. EPR measurements:

(a) TEMP-trapped ¹O₂ generated by biochar;

(b, c) BMPO-trapped •OH and O₂•⁻ generated by biochar;

(d) Hyperfine splitting fitting analysis of the 1KBC signal in panel (c).

Using the CIQTEK EPR spectrometer, the team identified reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated on the biochar surface:

-

¹O₂: strong TEMP–¹O₂ triple signal (1:1:1, AN = 17.32 G) observed only in 1KBC.

-

OH: BMPO–•OH quartet detected in both BC and 1KBC, but much stronger in 1KBC.

-

O₂•⁻: identified through BMPO–•OOH signals in methanol-containing systems.

1KBC produced significantly higher levels of ¹O₂, •OH, and O₂•⁻ than BC, confirming the enhanced redox activity induced by KOH modification.

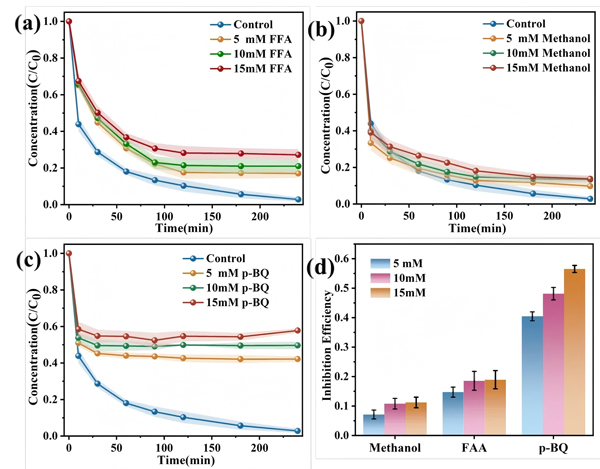

Free Radical Quenching Experiments

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of ¹O₂; (b) •OH; and (c) O₂•⁻ on Ni–Cit removal efficiency;

(d) Inhibition rates of different ROS on Ni–Cit removal.

By introducing quenchers, FFA (¹O₂), p-BQ (O₂•⁻), and methanol (•OH)—the team quantified the contributions of different ROS:

O₂•⁻ inhibition (55%) > ¹O₂ inhibition (17%) > •OH inhibition (12%)

This ranking indicates that O₂•⁻ plays the dominant role in Ni-Cit degradation and complex dissociation.

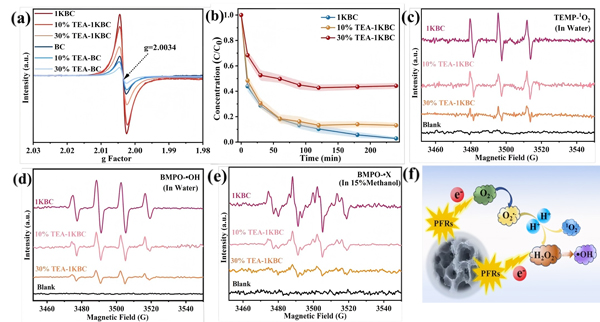

Role of PFRs and ROS Generation Mechanism

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Detection of surface PFRs in biochar;

(b) Effect of PFR quenching on Ni–Cit removal by biochar;

(c) ¹O₂, (d) •OH, and (e) O₂•⁻ signals in 1KBC and TEA-treated samples;

(f) Schematic of ROS transformation pathways.

Persistent free radicals (PFRs) in biochar are closely linked to ROS formation. EPR results showed:

-

1KBC exhibited much higher PFR concentration than BC.

-

PFRs had a g-value of 2.0034, characteristic of carbon-centered radicals adjacent to oxygen (e.g., phenoxy radicals).

-

Triethylamine (TEA) effectively quenched PFRs, reducing Ni-Cit removal efficiency to ~50% and drastically lowering ROS levels.

The mechanism (Fig. 6f):

-

Dissolved oxygen adsorbs onto the biochar surface.

-

PFRs transfer electrons to O₂, forming O₂•⁻.

-

O₂•⁻ initiates complex dissociation; subsequent ROS degrade the citrate ligand.

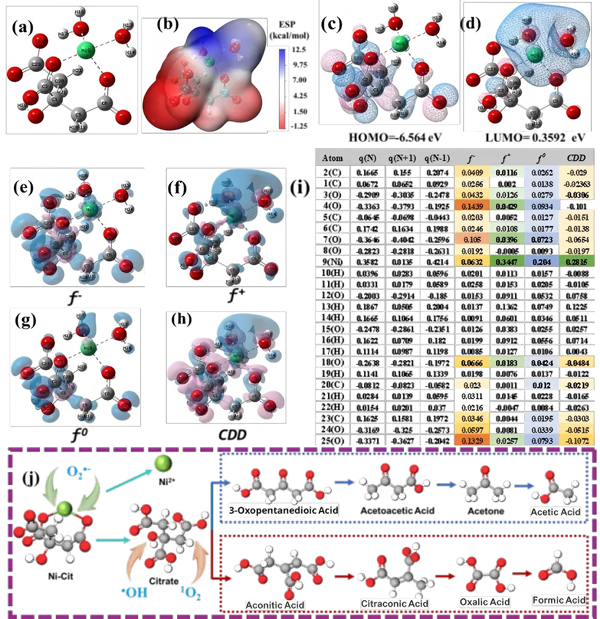

DFT Calculations and Mechanistic Insights

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(a) Optimized structure of Ni–Cit;

(b) Electrostatic potential (ESP) map;

(c) HOMO; (d) LUMO;

Fukui function isosurfaces of Ni–Cit:

(e) f⁻, (f) f⁺, (g) f⁰, (h) condensed dual descriptor (CDD), and (i) Fukui indices;

(j) Proposed degradation pathways of Ni–Cit.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations clarified the molecular reaction pathways:

-

Frontier molecular orbital and Fukui function analysis revealed that the Ni center is prone to nucleophilic attack, while the citrate ligand undergoes electrophilic reactions.

-

O₂•⁻, with its strong nucleophilicity, targets the Ni center, breaking the Ni–Cit coordination.

-

Citrate ligands degrade through two ROS-mediated pathways.

These theoretical results align with EPR findings and support the proposed mechanism.

KOH-modified biochar (1KBC) achieved 99.2% Ni removal from 50 mg/L Ni-Cit solution within 4 hours. The modification significantly enhanced porosity, surface functionality, and, critically, the concentration of persistent free radicals. These PFRs activated dissolved oxygen to generate ROS, among which O₂•⁻ acted as the primary species driving Ni-Cit dissociation. Subsequent ROS degraded the citrate ligand, while released Ni²⁺ was adsorbed onto the biochar.

This study demonstrates a sustainable "one-step dissociation and recovery" approach for treating metal–organic complexes, offering strong potential for future real-world applications.